Led by East Tennessee State University’s Dr. Justin Ledogar, an international team of researchers published a new study in April that suggests the earliest human ancestors may have ditched hard foods earlier than previously believed.

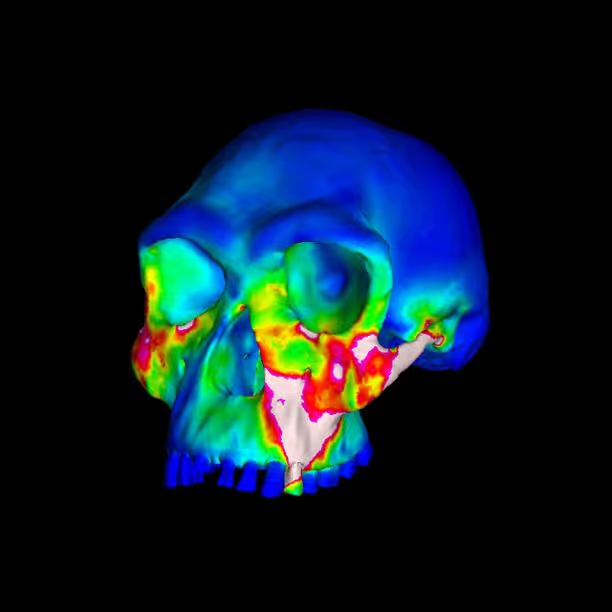

By utilizing advanced computer simulations, researchers were able to compare bite force mechanics of earlier human ancestors, recent modern humans, modern chimpanzees and Homo habilis – the earliest member of the genus Homo – by creating biomechanical models of their skulls.

Results show that Homo habilis was structurally constrained in its ability to crunch into hard foods with its molars — a limitation that persists in modern humans and offers fresh insight into the dietary adaptions and evolutionary developments that helped shape the human lineage.

The findings were published in the April 2025 edition of Royal Society Open Science.

“Our results point to a fundamental change in feeding behavior with the appearance of Homo habilis,” said Dr. Justin Ledogar, an assistant professor in ETSU’s Department of Biomedical Health Sciences in the College of Public Health. “The ability to process exceedingly hard or tough foods with high bite forces was reduced in Homo habilis compared with earlier hominin species.”

The study challenges the predominant view that a reduced ability to chew hard foods first evolved in Homo erectus, a later human ancestor. Modern humans face the same challenge as our earlier ancestors, which may help explain the prevalence of jaw joint pain today.

“Homo habilis probably couldn’t crack nuts or chew hard roots and tubers the way its predecessors could,” said Ledogar. “And that’s a kind of big deal—it suggests a major dietary shift was already underway at the dawn of our genus.”

The implications of the study extend beyond just diet.

As human skulls evolved away from high bite force production, it could have opened the door to changes elsewhere – potentially influencing speech, facial expression or brain expansion.

The study, titled “Bite force production and the origin of Homo,” is available online at https://bit.ly/4482jZA. To learn more about the ETSU College of Public Health, visit www.etsu.edu/cph/.

From innovative scholarship on vitamin deficiencies to the discovery of a giant flying squirrel, Ledogar is one of the dozens of ETSU faculty generating cutting-edge scholarship.